|

||

| Volume III, Issue III | Autumn 2004 | |

| Autumn 2004 Home Page |

| Culture/ Technology |

| Fiction |

| Music |

| Poetry |

| Theater |

| About / Contact |

| Archive |

| Current Home Page |

Eunuchs at an orgy: A critique of critics

A gloves-off, no-holds-barred critique of critics, our so-called arbiters of culture and the arts

On the cover of his recent book, "Hatchet Jobs: Cutting Through Contemporary Literature," New York novelist and book critic Dale Peck (right) is seen gripping a hatchet. It gets even uglier inside. Peck, who had a horribly traumatic childhood – he was abused by his father for being gay – has apparently decided to channel his understandable rage toward his father into his book reviews, which are at times violently hostile and typically reveal more about the critic than the subject of his critiques.

On the cover of his recent book, "Hatchet Jobs: Cutting Through Contemporary Literature," New York novelist and book critic Dale Peck (right) is seen gripping a hatchet. It gets even uglier inside. Peck, who had a horribly traumatic childhood – he was abused by his father for being gay – has apparently decided to channel his understandable rage toward his father into his book reviews, which are at times violently hostile and typically reveal more about the critic than the subject of his critiques.

Peck has verbally mutilated such established writers as Philip Roth, Terry McMillan, Julian Barnes and Rick Moody, whom he called the "worst writer of his generation." But people are starting to respond to his viciousness. While Peck was having lunch in Manhattan recently, Stanley Crouch, the novelist and jazz writer, introduced himself to Peck, who had slammed a novel of Crouch's a few years ago, then smacked him in the face. Crouch could face assault charges, but I don't suspect any right-minded jury would convict him.

"Dale Peck is a widely hated person in the realm of literature. He publishes reviews full of lies, and his sole purpose is to elevate himself," Crouch told CNBC after the punch was publicized. "I've gotten many telephone calls, so many commendations and accolades. For the first time I've been in New York, I feel like the people's hero."

Crouch's punch – well, it was reportedly more like a slap – packs a symbolic wallop. And I'm glad it happened. Now I'm not saying we should all start punching critics in the face when we don't like a review – I don't condone what Crouch did, or any violence against anyone, not even critics – but it would be nice to see them start swallowing some of their own venom now and then.

A wounded soul with incurable anger issues, Peck, whose reviews are noxious, snide, misleading and sometimes inaccurate, is clearly and unfairly attempting to exorcise his personal demons in the guise of legitimate arts criticism. And like so many of his ilk, Peck thinks his work is beyond reproach.

I say nonsense. I say it's time for more authors, musicians, actors, directors and other creative types who've been ripped to shreds by cruel, caviling critics like Peck to start hitting back.

I don't oppose arts criticism. And I'm not saying critics don't sometimes serve a useful purpose. Certainly they can assist a struggling musician, boost an obscure film or champion a deserving author. They can even provide valuable insight, at times. But the good they do is outweighed many-fold by their innate biases, their cruelty and, worse, their cluelessness.

Often more predictable than the masses they disdain, critics have tastes that simply do not reflect most of their readers or viewers. And I'm not talking about the lowest-common-denominator mainstream; I'm talking about the public that embraces movies, music, books and plays as popular entertainment, not sky-high art.

I'll allow that critics are not a collective, that they run the gamut from compassionate (too rare) to supercilious (too common). But after years of suffering through one self-righteous arts review after another, I've come to the easy conclusion that people who spend the majority of their adult lives criticizing the hard work of others are fatally flawed as humans and deserve and need to be criticized more often themselves.

Tragically, critics themselves are rarely challenged, other than in letters to the editor. Their work is never critiqued the way they critique others.

People complain about critics all the time, but rarely does anything come of it. There are nice exceptions, though. When director Arthur Penn released "Bonnie and Clyde," New York Times critic Bosley Crowther stupidly slammed the film, calling it "pointless." The letters came streaming in to the Times, which ultimately ran a glowing interview with Penn. Not long after, Crowther resigned. Good riddance.

People complain about critics all the time, but rarely does anything come of it. There are nice exceptions, though. When director Arthur Penn released "Bonnie and Clyde," New York Times critic Bosley Crowther stupidly slammed the film, calling it "pointless." The letters came streaming in to the Times, which ultimately ran a glowing interview with Penn. Not long after, Crowther resigned. Good riddance.

I mean, what is a critic's motivation in a bad review if not to damage the careers of the people involved in the art they are blasting? This one thankfully backfired on old Bosley.

When you think about it, arts criticism is a rather absurd gig, really. We all know that reviews are nothing more than one person's opinion, right? But if we as a society really believed that, critics wouldn't wield so much power. And, of course, power corrupts. Once critics gain a forum, be it in a nationally syndicated newspaper column, a local TV news show, an alternative weekly, or even some obscure online blogger site, they invariably adopt the untenable creed that they are espousing universal truth. Unfortunately, most critics don't really think of their reviews as one person's opinion. Most critics represent their work as gospel.

Who are these people?

But who are these people, these so-called arbiters of culture to whom we pay so much credence? Where do they come from? And what are their qualifications?

Typically, they're just journalists who have a particular interest in the art form about which they write. Nothing more.

Many reviewers you read now in the major dailies and national magazines came from the alternative weekly crowd. Entertainment Weekly's Lisa Schwartzbaum started at The Real Paper, and Janet Maslin and David Denby, from the New York Times, Vanity Fair's Stephen Schiff, and Entertainment Weekly's Owen Glieberman all came from the Boston Phoenix – and we all know how pretentious and how much attitude Bostonians sometimes possess.

Many reviewers you read now in the major dailies and national magazines came from the alternative weekly crowd. Entertainment Weekly's Lisa Schwartzbaum started at The Real Paper, and Janet Maslin and David Denby, from the New York Times, Vanity Fair's Stephen Schiff, and Entertainment Weekly's Owen Glieberman all came from the Boston Phoenix – and we all know how pretentious and how much attitude Bostonians sometimes possess.

But more than their professional backgrounds, what interests and concerns me are the personalities, predilections and predispositions of critics. And here's the painful truth: most critics I know – and I know a bunch – are dysfunctionally cerebral social misfits who are the very last people on earth I or anyone else should solicit for advice on anything having to do with passion or the human heart.

Adept at thinking, but failures at feeling, most critics I've met and observed are former high school nerds and emotional lepers who are socially deficient in one way or another. Typically embittered outcasts, their reviews are thinly veiled, cowardly attempts to exact revenge against a mainstream culture in which they never were fully accepted.

| Eunuchs at an orgy, most serious critics I've known are quirky, pretentious, dark-hearted, elitist nerds with bad breath and bad taste who dismiss pure joy sentiment of any kind and in virtually any art form unless it is couched in something artsy, oblique, obscure, subversive or 'socially significant.' |

Music, theater and film critics rarely have the courage or the ability to practice the art about which they write (Roger Ebert's screenplay "Beyond the Valley of the Dolls" is an exception, such as it is). Novelists, however, are the curious exception to this rule. Novelists often review other novelists' work. A bizarre and rather repulsive exercise in reverse log-rolling, and an obvious conflict of interest, this creates animosity, pissy jealousies, rabid competition and a deep resentment among many writers toward their peers.

Truth is, most critics have no idea what really constitutes a good book or movie or melody, because they too often mistake cynicism for intelligence, attitude for substance, anger for passion, obscurity for worthiness, and ambiguity for brilliance. Most critics love non-commercial, edgy, indeterminate art and scoff at normalcy, conventionality, sweetness and true love in art because these things are unattainable in their lives.

If it sounds mean and hypocritical, criticizing critics, well, so be it, it needs to be done. I hate critics' coldness, their cruelty, so I'm being a bit cold and cruel myself because they've collectively asked for it. They step over the line, all the time. They get personal, they get malicious. And while they can dish it out but good, they can't take it.

Sitting high on their false perch, God-like, dismissing or approving someone's life's work with a marginally clever phrase or a simple thumbs up or down, most of them don't have the stuffing to let their own work be judged. Filled with bravado in their reviews, critics turn into chicken-shits when their own work is challenged and analyzed the way they challenge and analyze others.

Most critics are not only cold and condescending, they are wildly insecure. You don't have to be a genius to know that people who criticize others incessantly are insecure. We all learned that in the second grade, if not earlier. Their arrogance, too, is an obvious sign of insecurity.

Among the most arrogant critics I've seen – and there's plenty of competition – is Internet movie critic T.C. Candler, who reveals on his Critical Mass web site what I think most critics actually believe about themselves: "Some may say that everyone's opinion is equally valid. I disagree whole-heartedly," Candler writes. "Ask yourself this question: Do you believe that the average member of the public is intelligent or dumb? I know what my answer would be. Oh, and if you are offended by that comment, well, just think about that for a moment."

Among the most arrogant critics I've seen – and there's plenty of competition – is Internet movie critic T.C. Candler, who reveals on his Critical Mass web site what I think most critics actually believe about themselves: "Some may say that everyone's opinion is equally valid. I disagree whole-heartedly," Candler writes. "Ask yourself this question: Do you believe that the average member of the public is intelligent or dumb? I know what my answer would be. Oh, and if you are offended by that comment, well, just think about that for a moment."

Candler continues, "There are two types of movie-going people, the 'Armageddon' crowd and the 'Schindler's List' crowd. I know where I stand ... and you probably know where you stand. I do believe that there are critic-proof people. Those people (The 'Armageddon' crowd) will never possess enough intellect or enough willpower to improve themselves, so that they may someday live up to Roger Ebert's challenge of 'arriving in triumph at above-average.' Most people would rather watch a popular movie than a good one. I truly believe the average moviegoer would have a tough time admitting that they disliked a huge box office hit because they don't want to seem outside of the herd. Most people are sheep."

Candler concludes, "This essay is not intended for 'Joe Schmos,' who wouldn't even make it past the first paragraph without getting tired of reading. Those people are not welcome on my site and don't deserve to have hard working critics laboring for them. To be completely honest ... They are not the demographic that most of my fellow critics and I are aiming for. We are not intended for the masses. Our readers should be serious about film, not obsessed with pop culture icons and flatulence humor. And maybe, just maybe, somewhere along the road, we can pick up a few of those souls who are teetering on the edge of a cliff, looking down on millions of blank-faced sheep, and lead them toward the enlightenment of exploration, curiosity and knowledge."

Candler's astounding elitism, his stupefyingly haughty attitude toward the great unwashed, is sickening enough. But even if he is correct that some people are sheep, and that mediocrity often does indeed reign, the real problem with his take is his almost Bushian with-us-or-against-us approach to art that says if you're smart, you can't enjoy a silly or dirty joke once in a while. I mean how depressing and wrong is that?

The only people I really can stand spending quality time with in this world – and critics almost never fall into this category – are people who know how and when to turn their brain on and, much more importantly, off. People who can indeed enjoy both a "Schindler's List" and an "Armageddon." You know, people like you, people who can watch and enjoy a "movie" but also a "film." People who have the ability to appreciate both the smart and the silly aspects of entertainment, and life.

If you can't laugh at a good toilet joke once in a while or amuse yourself by making a funny face in the mirror, it doesn't mean you are smarter or more enlightened than someone who can, it just means you're a humorless tight-ass who has sadly forgotten how funny it was when you farted in front of your parents' friends when you were 10.

| If you can't laugh at a good toilet joke once in a while or amuse yourself by making a funny face in the mirror, it doesn't mean you are smarter or more enlightened than someone who can, it just means you're a humorless tight-ass who has sadly forgotten how funny it was when you farted in front of your parents' friends when you were 10. |

Theater critics

Since I started reading newspapers and magazines as a kid, I've felt that artists of all kinds should return fire at critics who blast them – especially when the reviews are particularly derogatory and/or off-base. Critics need to hear more often from the folks they are hurting, offending or mislabeling.

I find it both amusing and frustrating that one critic can say emphatically, definitively, that something is terrific, while another can dismiss the very same thing as unlistenable. It seems to happen especially often with theater critics. As I've said, though reviews are just one person's opinion, most critics in their heart of hearts do not think of their own reviews that way.

Sadly, the fact that there are people out there who read and heed critics' advice – sometimes at the expense of their own instincts and judgments – is the reason critics start believing this about themselves. Whatever a critic does or says, though, no matter how high and mighty a reviewer gets, he will never be as high on the food chain as someone who actually creates something for a living.

At the end of the day, the one who can hold his head up the highest is the one who had the courage to stick his neck out and create something for all the world, including critics, to see, hear and judge.

A few years ago, an altogether dweebish San Diego theater critic named Pat Launer wrote a scathing review of a thoroughly enjoyable play consisting entirely of Burt Bacharach songs. In the review, the critic meanly and categorically dismissed Bacharach as a "'70s pop songster" who wrote "syrupy" songs. And she did it, nauseatingly, by using phrases from Bacharach's songs. Ugh.

A few years ago, an altogether dweebish San Diego theater critic named Pat Launer wrote a scathing review of a thoroughly enjoyable play consisting entirely of Burt Bacharach songs. In the review, the critic meanly and categorically dismissed Bacharach as a "'70s pop songster" who wrote "syrupy" songs. And she did it, nauseatingly, by using phrases from Bacharach's songs. Ugh.

Bacharach's music has touched millions of people for five decades. One of the best songwriters of the pop era – and most of his best stuff was in the '60s, not the '70s – Bacharach (left) is responsible for dozens of beautiful, evocative, deceptively simple, timeless songs with complex time and key changes that the critic probably doesn't even understand. Who was this local hack, who presumably never wrote a lovely song in her life, to dismiss that body of work with her mean-spirited and totally misinformed review?

What disturbed me most about her piece was its dark-hearted thesis that sweetness and sentiment are not legitimate concepts in theater. This common thesis among jaded critics in all genres is particularly maddening to me, given the fact that most of them are simply unequipped emotionally to comment on matters of the heart.

Movie critics

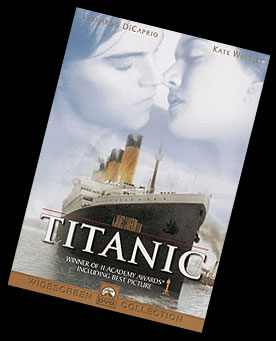

The Los Angeles Times' Kenneth Turan is a classic example of a painfully cerebral, nerdy, heartless, mind-over-what-matters type who unsuccessfully disguises his own disdain for the world with pithy little commentaries on filmmakers' passions. I was particularly enraged by his intense and repeated dismissals of the film "Titanic," a piece of work similar to Bacharach's music in its unabashed celebration of love, and life.

Critics like Turan almost always insist that sentiment in art is manipulative and unwelcome. Conversely, anything that lacks sentiment altogether is praiseworthy in most critics' books. But sentiment is by definition subjective, and in the final analysis, it is life. It's all about how much we choose to be manipulated.

Critics like Turan almost always insist that sentiment in art is manipulative and unwelcome. Conversely, anything that lacks sentiment altogether is praiseworthy in most critics' books. But sentiment is by definition subjective, and in the final analysis, it is life. It's all about how much we choose to be manipulated.

Sure, some movies and songs can lay it on way too thick, but without emotion, there is no art, and art by definition is manipulative. Sappy to one is sweet to another. Ironically and tragically, though, the people the very least qualified among all of us to be commenting on human emotion or sentiment are critics, most of whom are cynical, pretentious and afraid of their own feelings.

"Titanic" was an epic and amazing piece of work about love, individuality, survival and hope. I'm not saying you have to love the film, but if you were not moved by it at all, if it stirred no emotions in you whatsoever, you, like Turan, are dead where it counts.

Of course, on the other end of the spectrum you have the blurbmeisters, those critics who praise every movie just so they can see their names in the movie ads. These folks are ridiculous, too, but harmless. I'll take them, as shallow as they are, over someone like Mr. Cranky, a Web menace who hates just about every film ever made, including three of the best movies of all time: "Casablanca," "Star Wars" and "Cinema Paradiso." He's so negative, he's almost laughable. But what kind of childhood must this loser have had?

And what about all those nauseatingly pompous local "film" critics, the ones who don't work for major dailies but for alternative weeklies and pretentious Web rags who elevate film to an impossibly lofty, obscure level? It's just a movie, guys. They should all be taken out to the shed for taking themselves far too seriously to be taken seriously.

One such critic is the San Diego Reader's Duncan Shepherd, an intelligent and completely joyless doofus who finds fault with just about everything he sees. Duncan is so busy collating film minutiae that he is completely incapable of just enjoying the movie and, I suspect, life. Put your note pad down and just relax, Duncan. I beg you.

Music critics

As for music critics, most of them wouldn't recognize a simple good melody if it fell out of the sky and landed in their head. Matthew Webber, a music writer in Kansas who was a summer intern for Spin magazine, recently wrote a refreshingly stinging treatise on the pomposity of music critics, most of whom, he suggests, actually hate music.

"I've only worked in music journalism for three months, and already I'm jaded," Matt wrote. "I sympathize with people who think music critics are snide and unjust. I sympathize with people who ask, 'Why do they always rip my favorite band' and 'Why has every band I like become a guilty pleasure?'"

Loren Jan Wilson, a data network engineer at the University of Chicago who is in a band called Starlister, recently initiated a school project that combined a computer science background and a songwriting hobby with what she calls an "unhealthy obsession" for popular music reviews.

In it, Wilson attempted to come up with a new computer-assisted songwriting method which takes music critics' opinions into account. By writing software to statistically analyze the content of several thousand record reviews from the Pitchfork music Web site, she generated a set of compositional guidelines based on the musical preferences expressed by critics. She then used those guidelines to write and record a couple of original songs, discussing in detail the relationships between the songs and the data that she collected.

The compositional decisions she made as a result of the data she collected from critics' reviews included the following things that she says she would not have done with her own music: heavy use of sampling; distortion on vocals, guitar and drums; use of acoustic guitars; use of strings (violin, cello), and, of course, depressing/dark subject matter and mood.

The two songs she came up with through this fascinating piece of research of thousands of music reviews – "Kissing God" and "I'm Already Dead" – are both atmospheric, edgy, imitative pieces of crap that most critics would undoubtedly fall over themselves praising because, well, they just don't know any better. These are the same coterie of critics who think Lou Reed is a genius.

A few artists, though lamentably too few, have gone public with their disdain for music critics. Robert Lamm (right), for one. The longtime singer, songwriter and keyboardist in the band Chicago has written some of the best American pop songs of all time ("Beginnings," "Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is," "25 or 6 to 4," "Free," "Dialogue," "Saturday in the Park"), but he's never been a critical darling. At times, the nasty reviews have gotten to him.

A few artists, though lamentably too few, have gone public with their disdain for music critics. Robert Lamm (right), for one. The longtime singer, songwriter and keyboardist in the band Chicago has written some of the best American pop songs of all time ("Beginnings," "Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is," "25 or 6 to 4," "Free," "Dialogue," "Saturday in the Park"), but he's never been a critical darling. At times, the nasty reviews have gotten to him.

I've had several discussions with over the years about his problem with critics. Lamm has mellowed, as we all do with age, I guess, but back in the '70s he fired back, eloquently, by expressing his justifiable contempt in a song called "Critic's Choice," in which he wrote:

What do you want, what do you want

I'm givin' everything I have, I'm even trying to see if there's more

Locked deep inside, I'll try, I'll try

Can't you see, this is me

What do you need, what do you need

is someone just to hurt, So that you can appear to be smart

Keep a steady job, Play God, Play God

What do you really know

You parasite, you're dynamite

An oversight, misunderstanding what you hear

You're quick to cheer, and volunteer

Absurdities, musical blasphemies

Oh Lord, Save us all

What do you want, what do you want

I'm givin' every thing I have, I'm even trying to see if there's more

Locked deep inside, I'll try, I'll try

Can't you see, this is me

Trust me, most musicians feel this way, they just don't want you to know it. While Lamm vented his frustration toward critics emphatically, but cleverly, former Van Halen frontman David Lee Roth summed it up more succinctly when, while still in his former band, he remarked, "Most rock critics like Elvis Costello and not Van Halen because most rock critics look like Elvis Costello and not like me!"

As for Stanley Crouch's assault of Dale Peck, New Republic literary editor Leon Wieseltier, who published Peck's scathing review of Crouch's novel, acted as if he was utterly outraged by Crouch's behavior, which begs the question: Has Leon actually read Peck's nasty reviews? Does he really understand the hateful nature of one of his own writers?

"Hitting someone for something they've written," Leon said, "represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the intellectual's vocation."

Horse shit. Words are sometimes more damaging than fists. The "sticks and stones" argument has never worked for me. And reviews are personal. There is nothing more "personal" to an artist than his art. A person's art is an expression of his soul, and when some cretin condemns it, well, he's condemning the artist, too. And them's fighting words.

Web iconoclast Chuck Jerry, who also has serious issues with critics, was neither moderate nor measured in his recent verbal attack on critics. In a rant that almost reached the level of loathing of most critics – even that of master spewer Dale Peck – Jerry wrote, "Put all critics in a giant oven. Make them fight tigers, or all of them verses one elephant, or possibly a tiger and an elephant. No wait, a tiger riding an elephant. Maybe a combination of some sort of acids and a cool little acid squirting gun, but maybe some little bucket of some sort that's like resistant to acid, and we could pour it on them."

Of course, those who condone violence against critics need to chill. But I understand how they feel; I understand their anger, their frustration. Nonetheless, I do not advocate violence against anyone, not even critics. Well, okay ... maybe just a little bit of acid. And perhaps a baby tiger.

![]()

Autumn 2004 Culture, Politics & Technology Section | Autumn 2004 Main Page

Current Culture, Politics & Technology Section | Current Home Page

Copyright ©

Reprinted by permission of author, who retains all copyright and control.