|

|||

|

|||

| Home |

| Gallery |

| Culture/ Technology |

| Fiction |

| Music |

| Poetry |

| Theater |

| What's New |

| About/Contact |

| Archive |

|

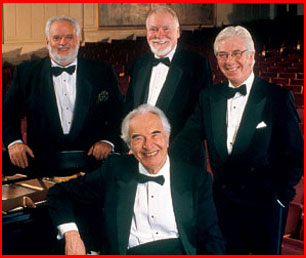

Not slowing down yet Published October 2005 If you're from San Diego County and you're talking to Dave Brubeck, be prepared to hear at least a little about his older brother. Anyone who's attended a music or theatrical performance at Palomar Community College in San Marcos has likely been in the Howard Brubeck Theatre. Howard, who died in 1993, was the longtime head of the music department at Palomar – a point Dave made early when called to talk about a recent appearance with the San Diego Symphony Orchestra.

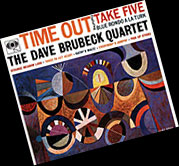

And yet, while casual fans may know Brubeck primarily for the hits that have become jazz classics from that album (primarily "Blue Rondo A La Turk" and "Take Five"), the fact is that in the four and a half decades since that album was released Brubeck has yet to really slow down. Composing, performing, recording – at 84 years old, Brubeck maintains a full schedule. "If you see my itinerary, you'll think I've gotta be working hard," Brubeck said by phone from his Connecticut base. "Most people couldn't keep up with me right now. I don't know how long I'll be able to last. The traveling is really tough. "We feel the only joy is playing; the rest is really tough work and it's so much harder to fly and takes so much longer at the airports" since 9-11, he said. He has a new album out on Telarc – "London Flat, London Sharp," which followed up last year's solo piano offering of World War II popular music, "Private Brubeck Remembers," which came out on the heels of 2003's "Park Avenue South." In fact, he's recorded a half-dozen albums of jazz and classical music on Telarc since turning 80. When the ballrooms starting dying off after World War II, Brubeck was one of the first to start booking gigs on college campuses, a practice he continues to this day. "We used to leave San Francisco and go to Tahoe or Reno and then Salt Lake City; there were three huge dance halls, maybe the largest in the world. Then the Electric Park Ballroom someplace in Iowa. A place called the Orchard Lake Ballroom in Detroit. We'd go right across the country playing in big ballrooms. I've toured with Duke [Ellington] where we played ballrooms and concerts right across the county. "We can do the same with campuses. It's become very good because the audiences are so aware. We've just played the the 50th anniversary of Jazz at Oberlin in 2003, and that was the first big breakthrough.

Today, Brubeck can afford a more leisurely pace. "Sometimes we go in and play three days, and play with the jazz band on campus. We just played in Jacksonville, Fla. – a wonderful jazz band." And while Brubeck said he appreciates the opportunities the Indian casinos are offering jazz musicians to play in front of live audiences, he said he's not sure it's the right environment for his audience. "Some years ago, I worked in gambling casinos at Tahoe and Las Vegas, but it wasn't a good environment in some ways. The people had to walk through all the gambling to get to the concert. And some of my friends lost a little money on the way to the concert. And I guess some gained a little. I thought it wasn't quite right, but it could be, if they'd really separate it." Unlike many musicians of his generation who pine for the old days, Brubeck likes what he hears today, particularly the growing international influence on jazz. In fact, Brubeck says he wrote an article for Downbeat magazine in 1949 that predicted jazz would reach beyond America's borders. "I said in that article that someday you're going to hear Chinese trumpet players, Japanese, Indian. Look at the recordings I made – 'Jazz Impressions of Eurasia.' That was 1958. "(Jazz) started in New Orleans in an international way, right from the beginning. All you have to do is read up on Jelly Roll Morton. He was talking about the French Opera House influence. "The first blues starts with a tango, W.C. Handy's 'St. Louis Blues.' "In India, we were a big success because Indian classical music is 90 percent improvisation, and they really went for my group and especially (drummer) Joe Morello. They were amazed." As far as the ongoing issue of race in music, Brubeck said he never experienced any backlash for being white and playing a music invented by blacks. "Race never bothered me. I'm a Duke Ellington fellow at Yale, and Duke wanted me. Look at the recording I made with Louis [Armstrong], Jimmy Rushing, Carmen McRae." In the vein of playing with other jazz luminaries, Brubeck brought up the interesting point that he and nonagenarian pianist Jay McShann – a contemporary of Count Basie in the pre-war Kansas City jazz scene – had crossed paths on the road for decades, but had never met until Clint Eastwood brought them together for a segment in Martin Scorcese's 2003 TV documentary, "The Blues," "Piano Blues."

"I've known Clint since he was quite young. He used to come in where I worked in Oakland, when he was 15 years old." One of Brubeck's main interests now is the Brubeck Institute at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, which houses a permanent archive of his private papers. "It's going great," he said of the institute. "This is the fifth year coming up. It's called a 'living archive and institute.' They do a lot of my music at the conservatory and with the Stockton Symphony, and then many students keep my music going. So there's a lot going on." As for his own status in jazz, Brubeck dismisses any notion he is a "legend." "I don't consider being a legend; I just work." |

Copyright © Turbula.net

"Sometimes we played 100 colleges in a row right across the country," he said. "And that took the place of the dance halls."

"Sometimes we played 100 colleges in a row right across the country," he said. "And that took the place of the dance halls."