|

|||

|

|||

| Home |

| Gallery |

| Culture/ Technology |

| Fiction |

| Music |

| Poetry |

| Theater |

| What's New |

| About/Contact |

| Archive |

|

This Poisoned Paradise April sat hunched forward with her back against the roundhouse wall and her knees pulled up under a coarse blue cotton poncho. She wept softly, with the measured pace of one who has been at it for a while. She was ten years old and she could cry for a long time.

Out on the sand in front of the house, April's four-year-old sister Dawn played as if nothing had happened. A mile of smoky sand stretched out in front of them, from the house down to the faint blue razor line of gulf water. Dawn dug her hands into the sand and pushed it into mounds in front of her. "Dirty sand," she said. She had heard one of the adults talk about the sand. It looked like a white carpet that had been stained by foot traffic and needed a steam cleaning. "Dirty sand." Inside the roundhouse, the adults sat talking, keeping their voices low. It was unusual of them to gather inside while the sun still hung over the beach. Normally, they would only huddle inside under the roof fronds during the rainy season. And even then, they would entertain themselves with board games and crude accapella karaoke. "How long do you think Rich will be gone?" Leeann Kerry asked her brother Ross. "He's gotta go to Mexicali," he said, "it'd be nice if they had a real police station in Felipe, but they don't. I've been there. It's not even good enough to be called a hole in the wall." "Shouldn't we do something about Jimmy? I mean, it doesn't seem right to just leave him out there. Laying on the sand." "We put a tarp over him," he replied. "I know, but what if some drunks out cruising the beach stop and lift up the tarp, just to see what's under it?" "What if a little one comes along and takes a peek?" Ellen Kerry said from her folding chair by the window. She was "Gramma," mother to half the adults and grandmother to most of the children in camp. Jack Hunt sat coddling a beer bottle at the concrete bar across the room from Gramma. White-haired and white-bearded, he looked like a aging walrus. His sons played with Gramma Kerry's sons in the same sand outside the roundhouse thirty years before. Back then, there were still outhouses on the beach and the only motorized toys in camp were the trucks which carried them on the two hundred and fifty mile journey down the finger of Mexico to San Felipe. "Ellen's right," he said. "You need to go move him, Ross. Put him in the back of your truck, and bring him back into camp." Ross married only six months before this trip. His bride, Janell, sat next to her mother-in-law at the bar. Because she was pregnant, she was the only one not drinking alcohol. She sipped a ginger ale, and looked at her husband. He looked back at his father with level gaze. They all worked construction. Jack Hunt's outfit put roofs on the houses built by Kerry Construction. His son Ross ran a crew for Kerry Construction. They were part of the Kerry clan, only their last name was different. All of them worked the whole year to travel down for a week on the beach, where there were no deadlines other than drinking the last beer opened to get to the next. "All right," Ross finally said, and got up from his chair. Janell rose up slightly to dismount clumsily from the bar stool. She joined her husband at the door. They walked outside together, and stood on the concrete slab porch, looking out into the azure distance. Ten minutes after Ross left and Janell came back inside to reclaim her bar stool, Bill Kerry appeared in the doorway. "I told Amy last year that we should take those poles down," he said loudly, "people can either put up a temporary net or play volleyball at the beach bar in town." He was the family patriarch since his father passed three years before. He inherited Kerry Construction and leadership of the clan. He enjoyed his role immensely. He had been preparing for his ascension for years, entering rooms full of people like this, standing outside and talking to focus all attention on himself as he entered. In this manner, he took over the conversation naturally, without it seeming intentional or self-serving.

He was his mother's Irish son, and his voice had the charm of the old country, while his eyes went from face to face like a Southern traveling minister, until everyone in the room felt included. "It was only a matter of time before something like happened," he concluded, waving his brown bottled beer as benediction. "Well, I always felt like motorcycles roaring around camp was asking for trouble," Gramma Kerry echoed her number one son. Ross came back in through the open door and sat down. Jack Hunt went and got him a beer. Ross took a drink, but put the bottle down on the table when he noticed how badly his hand shook while holding it. Bill Kerry kept talking. "I should have gone with Rich," he said. "But I saw Mauricio was driving, and I just automatically avoid going anywhere with him because he stops at so many houses on the way when he goes anywhere. It usually takes me a year to forget the last trip, and get drunk enough to climb into a car with him again." Leeann Kerry looked over at him in alarm. Mauricio was the Mexican landlord of the beach. The Mexican legal system is part feudal, part Biblical. Forty years ago, land grants were based on preferment, and procreation. The governor gave Mauricio's father the original land grant; one kilometer of beach for every son. Mauricio's father had four sons, so he ended up with almost two miles of beachfront property. Mauricio ran the family business now. He had allowed Bill Kerry to pour the slab for the roundhouse. It was a rare concession. He made money by building the beach houses, as well as collecting yearly rent on them. Over by the back door, Bobby Kerry bent over the thick cardboard boxes that the Mexican beer came in, building a staging point for the bottles, packing them away for the eventual trip back to the sub-agencia. "We might not even be in this spot if you guys hadn't been running a tourist hotel," he said to Ricky Hunt, who sat next to his brother Ross. Bobby was drunker than everyone else in the room, as usual. Over on his bar stool, Jack Hunt bristled at Bobby's remark. "What's that supposed to mean?" he asked. He might've been a fat, white-haired old walrus, but even an old walrus has weight enough to be dangerous. "Hush, Bobby," Gramma Kerry snapped. He was her son too, and she knew how he could be. But Bobby continued on. "I mean you're running a bed and breakfast over at your place." His drunken voice had a strange western lilt to it, like a tenor cowboy &#!50; strange for a man who grew up twenty minutes outside of San Diego. "What did you get from Jimmy, twenty or thirty bucks?" "Hey, that's a contribution for the water tank," Ricky Hunt said. "Yeah, sure it is," Bobby sneered, "well, I guess beer used to be water, huh?" His father died of cirrhosis. Matt, his next oldest brother after Bill, fell to his death out of a pine tree he climbed while drunk to prove he wasn't too old to do it. The family blind spot was no particular secret. Jack Hunt was halfway off his barstool when Gramma Kerry stopped him short. "Jack," she said. She got up and walked over to stand in front of her errant son. "And you stop it, Bobby," she said firmly, "this is not the time to be talking about money." "Yeah, shut up, grass cutter," Ricky Hunt said from his seat across the room. Reminding Bobby he had landscaped in the past to pay his family's bills was like slapping him. He bolted up out of his chair, butting against his mother, who fell backwards. Jack Hunt lept forward to catch her before she hit the concrete.

Gramma Kerry stood up with Jack Hunt's help. He walked her back to the chair by the window. After seeing her comfortably situated back in her chair, he went over and wrapped an arm around Bill Kerry's shoulder and drew him outside onto the porch. Jack sat down on the concrete step and put his feet on the sand. Bill stayed standing. He looked over to where Dawn played in the sand. She was his youngest child. Scooping the grey sand into pails, she packed them with her palms and then upended them, trying to build castles with dry sand. "The tide'll come up in a couple hours, honey," Bill said, "then you can make a real sand castle." "I wonder if the federales will get involved," Jack said. "Maybe they will," Bill replied, "death is a pretty big deal down here." The legal system in Mexico has no writ of habeus corpus. You can sit in a Mexican jail until you die. The Kerry/Hunt family members inside the roundhouse had heard the gossip from other Americans drinking at the bar in Felipe. They said that if you got into a car accident with a Mexican national you didn't know, it would be best just to abandon the vehicle and start heading for the border. Gramma Kerry came to the doorway. "Come on back inside, now. Bobby says he'll behave." "There's too many people in there," Jack Hunt said. "Your family's in here," she replied, "we need to be here for Rich when he comes back." "They're not going to charge him with anything, Ma," Bill said. "Well, I hope not. But you know what I mean." Bill did as he was told, and Jack Hunt stood up and followed him. The roundhouse was over twenty years old. Gramma Kerry was saying that the thatched roof was developing leaks, and that it would need to be replaced soon. "I wonder if they would let you get up there and help them re-roof it," she said to Jack Hunt. "I don't know," he replied, "I'm an old dog who's more used to tarpaper and shingles than sticks and palm fronds." On the wall between the propane fridge and the back door, four or five black-and-white photos lay pinned to a board mounted against the brick. Bill's and Mauricio's fathers grinned out of the cab of an old pick-up in several of the pictures. Another photo showed a circle of old pick-ups – Fords and Dodges, parked in a circle on the grey beach sand. The pick-ups had camper shells and clotheslines strung out with towels drying. Outside the roundhouse, Dawn filled buckets with the grey beach sand and looked down at the blue line in the distance, waiting for the water that would turn it into sand castles. Published June 2006 |

Copyright ©

Reprinted by permission of author, who retains all copyright and control.

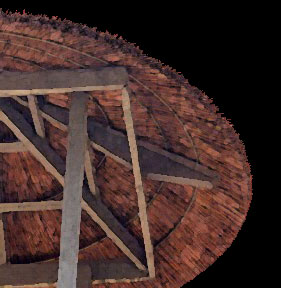

The roundhouse was constructed with the peculiar Mexican brick specific to Baja. The clay used for the brick is fired with oxgen trapped inside and it explodes in the kiln, creating swirling bursts of white and orange in the brown. The bricks were laid on their sides and cemented in place with the loose gray cement of a portable mixer. A stripped tree stood in the center of the house. Lumber struts fanned out from it's top; two-by-fours stained brown with age. Palm fronds, dried by the sun and the years, were woven into a thatch and laid over the wooden umbrella to form the roof.

The roundhouse was constructed with the peculiar Mexican brick specific to Baja. The clay used for the brick is fired with oxgen trapped inside and it explodes in the kiln, creating swirling bursts of white and orange in the brown. The bricks were laid on their sides and cemented in place with the loose gray cement of a portable mixer. A stripped tree stood in the center of the house. Lumber struts fanned out from it's top; two-by-fours stained brown with age. Palm fronds, dried by the sun and the years, were woven into a thatch and laid over the wooden umbrella to form the roof. "Let's see," he continued, "how many quads and dirt bikes roll through the sand out there between sunrise and darkness?"

"Let's see," he continued, "how many quads and dirt bikes roll through the sand out there between sunrise and darkness?" "Don't you hit my mom!" Bill yelled, and jumped on his brother. The two sons wrestled and strained against each other beneath the timber beams and the propane lanterns hanging from them. Bill looked like he was crying with rage. He was not as drunk as Bobby and he suddenly lowered a shoulder and brought it up into his brother's face. Bobby staggered back and fell onto the stone seat in front of the crude fireplace. He lay there, breathing hard.

"Don't you hit my mom!" Bill yelled, and jumped on his brother. The two sons wrestled and strained against each other beneath the timber beams and the propane lanterns hanging from them. Bill looked like he was crying with rage. He was not as drunk as Bobby and he suddenly lowered a shoulder and brought it up into his brother's face. Bobby staggered back and fell onto the stone seat in front of the crude fireplace. He lay there, breathing hard.